INDUSTRIAL GARDENING

Up near the top of the list of things I knew I would never own; just under the Lear jet and the yacht berth in Monaco harbour, was a ride-on lawn mower. It maybe OK for a bloated banker in Godalming, but us horny-handed sons of the soil pushed mowers . In the U.K., we used a little Flymo rotary job that was very cheap and each one lasted about four or five years.

When we moved here, we started off with a manual cylinder mower, which we bought in a back to nature moment, to avoid the sound of civilisation. Cami valiantly struggled with it for a few weeks, before we realised that it just wouldn't cut it. I am sure that it would cut grass O.K., but our mixture of grass, weeds, nettles and rocks, no. We moved on to an electric rotary mower, which did a good job of those areas which were mainly grass, but would not get near the vast area out behind the barns. We tried to keep that under control with a scythe and then a brush cutter, but it just took forever.

There comes a point where you have to accept reality: So here she is on the left, Gladys, the grass cutter.

She mows, hauls logs and carts compost and earth around. She rides roughshod over the wilderness and after only about an hour, makes it look almost civilised. It is a bit of a hairy ride at the moments as Gladys bucks and slides over the rabbit and mole hills and drops into the holes where large rocks have been removed, but we will slowly level things out with about three tonnes of a sand and compost mixture.

Next to Gladys is her good friend, General Tojo, planet terra-former. Just as an underpowered mower is no use to us for lawn maintenance, so a border fork won't get near to digging the ground over for vegetable growing. It is sand at the top, over heavy clay that has never been dug before. First time round, it has to be dug by hand in order to remove the boulders and broken wine bottles, but after that General Togo can break up the soggy stuff at the end of winter and then we can keep everything under control with the usual assortment of spades and forks, plus some exploding devices for the mole tunnels.

To round out our collection of industrial strength gardening tools, we have a selection of line strimmers and brush cutters, plus a couple of chain saws.

The line strimmer at the back is a battery powered model for tidying up around flower and vegetable beds, but the real work is done by the two petrol powered units. The yellow and black Ryobi 4 stroke is fitted with a line strimmer head and the orange Stihl 2 stroke has a brush cutting blade. The Stihl will power its way through dense undergrowth without effort, cutting through inch thick bramble stalks and chopping bindweed into shreds. It also destroys large ant hills and, at a pinch, will level out undulating ground. It is the model that the local council uses to clear out drainage ditches and because of its weight, you have to support it clipped to what looks like a bright orange bullet proof vest.

With the amount of trees and large shrubs we have, a chainsaw is essential. We have his & hers models. A battery powered one for Cami to keep things under control and a petrol model for managing the trees, cutting firewood and massacring people from Texas.

Big old trees require considerable care and attention to keep them in good health. Storms break off branches and the tree needs to be kept balanced so that it doesn't lean too far in any one direction.

Last year, we lost one of the ancient ash trees to a storm and the complete tree needed chopping up. Here is the pile of logs it made, most of which were sawn by our good neighbour Guy, whose garden it landed in.

Tree lopping round here is done by driving one on the tractors up to the tree and hoisting someone up on a platform attached to the front forks. I haven't tried that yet, but here is christophe, our neighbours son in law, hacking away with a chainsaw. Somewhere in there is the electricity cable feeding two houses, which he is clearing before EDF come and charge us for doing the job.

This being rural France, he is taking all necessary safety precautions for working at height, with a chainsaw, next to a live electric cable. He is wearing wellington boots.

So, gardening, which was always a straw hat and dibber activity for me in England, has become a red in tooth and claw, petrol powered struggle against virgin wilderness.

Wild wolves have been sighted in the next department and their arrival here will happily complete the picture of us as pioneers, taming the un-trod reaches of Europe.

FINALLY SOME WOODWORKING

I moved all my woodworking tools over here in 2012, but, up until recently, I haven't had a chance to use them seriously. I thoroughly enjoy the small scale building work involved in renovating an old house, but the thing which gives me most pleasure after sex, drugs, rock & roll, eating, drinking and reading is working with wood.

Living in France is perfect for a wood junkie as 25% of the land area is still covered by forest and the price of timber is much less than in the U.K.. Here in the Limousin, there are a variety of hardwoods available, but the signature tree is the Oak. I get my oak from a sawmill about 20kms north of here and it is all culled from local forest and air dried on site. It comes as sawn planks, mostly 30mm and 40mm thick and as wide as they can get out of the tree. They will rip it to any width you want, but are reluctant to fuss about cutting it to length. Just mooch around the yard until you find some roughly the right length. I usually just get them to rip full, bark to bark planks in half, so that I get one straight edge.

The thing about timber is that as it dries from about 40% moisture by weight in a just felled winter log (in the summer, the moisture content can be above 50% with all that rising sap business), down to the 10% or so that I need, it changes shape depending on how it grew in the first place, how it is sawn and how it is dried. The first stage of drying is just to leave the felled logs lying about, which will get rid of most of the "free" water, i.e. water not chemically bound to the tree. Then the logs are sawn into planks, which are then either carefully stored to dry in the air, or dried in a kiln. I won't go unto all the details of the different ways to saw a log, but quartersawn is best.

It is during the drying stage that most of the changes in shape take place and these will happen no matter how carefully the sawn planks are stored. A plank can bend across its width, called cupping, bend along its length, called bowing, or try to turn itself into a corkscrew by twisting. Most planks end up with a combination of all three shape changes, which is why, to reliably get a 25mm thick plank, you need to start with 30mm and to get 32mm, you should buy at 40mm.

In the U.S. timber thickness is traditionally expressed in quarters of an inch. So one inch thick is four quarters and 40mm is just over six quarters. Another nice old measuring system that needs preserving.

As well as all this warping, you will also get knots becoming loose as they shrink, straight edges that become wavy and all manner of cracks and breaks, particularly at the end of planks. You might be wondering at this point why we bother to work with such messy material, well, I'll tell you. Once you have wrestled it into shape and created something useful or beautiful or, if you are really lucky, both useful and beautiful, the feeling of satisfaction is like nothing else.

The most important things that I have made so far in France are a set of window sills for the new kitchen and a mantle-piece for the living room. In both cases, the joinery is very simple and the real work is getting the timber flat, square and smooth.

Everything starts at the table saw.

On the left are planks that have been acclimatising to the ambient humidity of our house for some weeks and on the right, one of them is getting its waney edge sawn off. The waney edge is the bit with bark still on it.

Once it is sawn into planks of roughly the right length and width, it is time to start flattening and straightening the timber. I do have a 200mm jointer for flattening the face of a plank, but as most of the planks are at least 250mm wide, that is not a lot of use. Instead, I turn to my trusty set of hand planes.

The smoothing and block planes in the rack are all set to different levels of cutting aggression, but are all honed to the same bevel angle. The plane on the right hand end of the rack is a scrub plane, which is used to quickly take off large amounts of wood, leaving a scalloped surface, which can then be smoothed. For a board which is heavily cupped or bowed, it is the go to plane at the start of the smoothing process. The picture on the right shows how it is usually used, across the grain, taking off large chips of wood.

Half an hour spent scrubbing a two metre long plank is as good exercise as your expensive gym membership will give you. If you do it properly, locking your arms and using your trunk and legs to power the plane, then the whole body gets a workout.

The two planes on the right are the big brothers, with a 600mm try plane, (also called a jointer plane), at the back and a Lie Neilson jack plane in front. The jack plane is usually the last plane to touch the board and is set to take a very fine shaving. It is the most expensive modern plane I own, bought with some bonus money when I was a foot soldier in the Oracle and SAP database trenches.

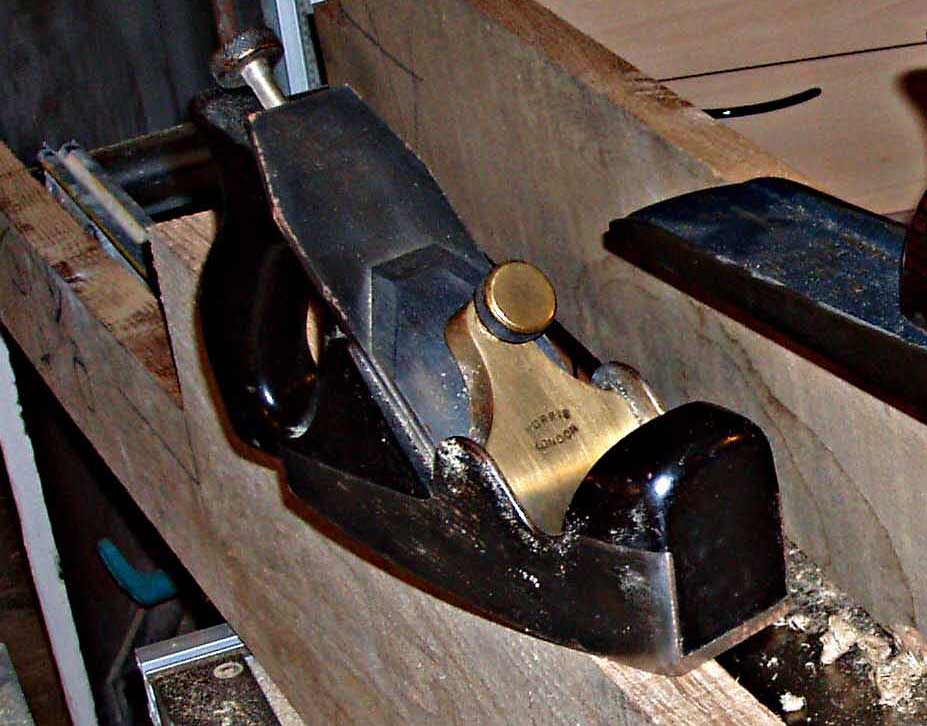

However, the jewel in my collection is this early twentieth century Norris smoother. It is called a coffin plane, because it is shaped like a coffin and has a really thick blade that takes a beautiful edge.

An interesting thing happens during the smoothing process. The words change. Planks become boards and timber (lumber if you are in the U.S.) becomes wood. The growth rings that you study in timber become the grain and figure that you contemplate in wood. It's not a universal truth of course, but generally that is what happens.

At the end of the smoothing and flattening process you get something like this:

Three boards butt-jointed together to make a 600mm wide window sill. It just needs the front edges rounded over and a couple of coats of wax.

The French divide woodworking into three types of activity: Charpenterie, which is construction work, from where we get the word carpenter; Menuiserie, which is the making of furniture and ébénisterie, which is the fine detailed work. The word ébénisterie is derived from the use of ebony for inlays and edging, which has always been an exotic and expensive wood.DRAINED

I'll bet there aren't many of you reading this that have given a lot of thought to drains, well I have spent the last two years thinking constantly about them .

When we first moved in, all drainage went to a farm slurry pit via a series of old clay drainage pipes. The kitchen sink drain ran via an open gully at the front of the house, before disappearing into the pipework.

Once we had installed the fosse septique (septic tank), we diverted all of the bathroom and toilet drains to it, but not the kitchen sink as we intended to move that out of the main kitchen/living room and into the back kitchen that I was converting from the old cellar.. You've probably forgotten, so I'll remind you that the cellar is on the ground floor, had its own front door and stairs to an attic area.

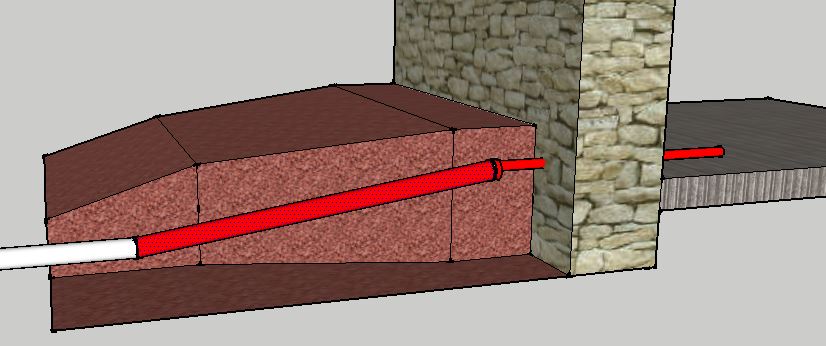

Anyway, before I could install a sink I needed to run drainage to connect with the fosse and it was by no means clear that this would be possible. It is all a question of levels and the way that pig pens had been built at the back of the house. I think a diagram is needed to explain the problem.

To the right of the wall is the kitchen floor which, as you can see, is below the level of the floor in the pigpen that is built to the left of the wall. The white tube was laid when they installed the fosse and the red pipe is the drainage we need to run between that and the new kitchen sink. At the moment, there is no door or window in the wall and I was not certain that the pipe from the fosse was below the kitchen floor level. Why couldn't I just raise the pipe in the kitchen? Well, it had to pass through a concrete step that connected the kitchen to the living room and was only 100mm tall.

So the first job was to dig out some of the pigpen floor and drill a hole through the wall. It was then possible to take levels from each end of a rod pushed through the hole and thus establish that we had just enough fall for the drain to work properly. The backup plan, had the levels not worked out, was to install one of those drainage pumps that allows you to pass waste through small bore pipes. However, I am a great believer in avoiding mechanical solutions if they can be avoided, so I was pleased that it all worked out.

Here is the finished drain exiting the pig pen, which will eventually be knocked down. In the meantime the drain will be buried in sand.

The spur on the left is for draining the central heating boiler.

A KITCHEN RISES OUT OF THE CELLAR

You may remember from my earlier notes that our house is really two houses. The main one and a small one attached to it with just one room on the ground floor, described as a cellar in the advert, with a steep staircase leading to an attic.

This shows how they go together. The main house is on the left, with the smaller house leaning up against it and a couple of the many pig pens on the right. You can also just see our two storey barn poking up at the back.

The thing I noticed on my first visit to the property was that there was a large cupboard let into the wall between the two houses and that was the key to unlocking the potential of the little house. Once I had torn out the cupboard, there was only a 100mm brick wall between me and the cellar and, as there was already a large oak lintel above the cupboard, it was a quick job with a sledge hammer to make an opening.

Last year I turned the rough opening into something a bit more civilised. I created the arch with a plywood former and some lightweight blocks and then gave it a skim coat of lime plaster.

Needless to say the two floors were not on the same level, but I was able to make a well-defined step.

The next job was to replace the solid wood front door with a window to let more light into the area. Because the wall is East facing and because I had lots of electric cable and water pipes to hide, I decided to doublage the lower part of the wall, up to window sill height over most of the wall and floor to ceiling where the door had been. Doublage is big in France and simply means adding a second wall to either the inside or outside to improve insulation.

I added 200mm to the 500mm wall. 100mm blocks and 100mm of Rockwool stuffed between the two walls.

Where the doorway had been I needed to build the complete 700mm thick and here are the first blocks being cut to size and laid out.

Here is the new window getting its first fitting. It is straight and level, but the old door opening isn't. Seeing this picture reminds me that I must get Jean Marie to move his bloody hay bales as they are spoiling my view over the valley of the Brame river. I mean, what does he think this is, a farm?

We also replaced the two small windows. The old one is on the left by the way, just in case you were wondering, and brightened up the whole area inside with white lime on the walls and four coats of high opacity white paint on the beams and ceiling boards.

Finally we needed to cover the floor and I was really looking forward to this as there is something very satisfying about laying floor tiles, particularly in seeing a pattern emerge.

Whilst I had been careful to lay a flat and level concrete slab, I had deliberately not smoothed out the small ridges left by the tamping process. So I first poured some self-levelling mixture to fill in any small imperfections and smooth out those ridges.

The room is L shaped, so it was easy to do the job in two halves, which is important for an old boy like me as mixing up the 25kg bags of compound and lugging the huge buckets of wet stuff is bloody hard work.

You always start tiling away from any walls, but in this case, because I had a pattern to contend with, I also had to figure out how to make the pattern end up equidistant between the unit on the left and the row of units that would be going on the right.

Well, here goes. The first tiles are glued in place. No going back now.

The first half of the room complete. All I need now is some peasant washerwoman to come and clean up after me. Where is Camilla?

By the early part of this year, we were ready to start putting the kitchen together and finally get rid of the sink unit in the living room. I say sink unit, but the unit part disappeared very soon after we moved in, as it was rotted and smelt like some old swamp. I hoisted the sink off and built this temporary support.

The word temporary can mean almost anything you want in terms of timescale and in this case, it meant three years. But, on the bright side, some parts of the house look even worse than this.

And here is the end result; one corner of the new kitchen. Not quite finished yet; needs doors and kickboards on the units and the wall tiles need grouting, but it is in use, with no problems so far. There is still a lot to do in the rest of the kitchen, but it will slowly come together and by the end of this year, we should only have the new back door and staircase to the loft to complete.

This is the latest design for the back door and staircase. It raises the door about 200mm above floor level, which solves the problem of the ground level outside and still leaves enough room for a 600mm wide stairway and millers ladder to the attic area.

LIFE AS SHE IS LIVED

So, after four years of life in rural France, two of them full-time, what do I think of it all? Am I one of those crashingly boring English expats, constantly wittering on about the lack of good tea and Marmite, or am I slowly morphing into a French paysan, full of gallic shrugs and a healthy disrespect for anyone from Paris?

I thrive on change and uncertainty; probably some nomad genes expressing themselves, so moving to a new country, where I can barely make myself understood concerning the simple things in life, held no terrors for me.

Of course, I never move into a new situation blindly and I had done lots of research on living in France and, more particularly, renovating buildings in France. I did innumerable calculations on the cost of materials and labour and had a fully worked out three year renovation plan, which is probably going to take about six years to complete, but will come in on budget. I also brought with me a bi-lingual French wife and a couple of credit cards that are good for anywhere on Earth.

We have not suffered from any of the horror stories of French bureaucracy that we read about on expat web sites. Our experiences of local planning and building control, vehicle registration, health service registration and local authority taxation have all been positive, with friendly, helpful people trying their best to fill in the gaps in our understanding. Yes, France is minutely regulated, but at least, thanks to Napoleon, it is all logically organised and consistent, unlike the English system, which, whilst having far fewer regulations, is a mass of exceptions and Spanish practices.

There are 400,000 "Normes" (regulations covering building, manufacturing and sale of goods) in France: One of them covers the slipperiness of mineral based flooring products if you walk on them in bare feet. There are 23,000 pages in the Official Journal (working practices for civil servants) and the employment regulations weigh 1.5 kilograms.

We have also been amazingly lucky landing up with the set of neighbours we have in Montgomard. There are nine of us living in the hamlet, which is in the middle of a cattle farm and, apart from Cami and me, everyone is related by blood or marriage. So there is a real family atmosphere and we have been taken in as part of the family. They were all a bit wary at first, but in no time were chatting away to Camilla and shaking my hand or kissing me every time we met. There are regular visits from members of their vast extended family, which involves a lot more kissing and hand shaking. Kids are dumped here during school holidays, more kissing and hand shaking and there is a constant stream of delivery drivers, posties, plumbers, builders and farmers, which of course involves… yes, you guessed it. It is a very tactile country and, outside of Paris, an amazingly polite country.

I am struggling with spoken French still. I can now read the language reasonably fluently, particularly if the subject matter is drains or fitting solar panels, but being somewhat deaf, I cannot often hear clearly what people are saying and without hearing it, I cannot comprehend it. I have turned off the hard of hearing subtitles on the television to force myself to listen to the language, but I think it's going to take another couple of years before my ability to speak French catches up with my ability to read it.

What I have realised, somewhat surprisingly, is that I am a country boy at heart. I grew up in south London and for most of my life have lived in towns and cities. The majority of my adult holidays have been spent in cities and I have appreciated all that city life has to offer: The pubs and restaurants, art galleries and museums, cinemas and book shops, not theatres though, but almost everything else.

Here, smack bang in the middle of the French countryside, there is none of that and, do you know what? I don't miss it. I sometimes wake up in the morning to nothing, no sound; no traffic, no people, no aircraft overhead and then a bird will sing and I smile.

Yes, I think I can survive this existence for a little while yet.