Back in the rat race

We arrived back in England at the end of July and the first thing I noticed was how alienated I had become from English drivers in five short months away. As soon as we slid off the train onto the M20, I could feel the agression, the incipient road rage, the careless disregard for other road users. Three lanes of rat maze in each direction with no cheese at the end. The best "rat" quote I have come across is this: "The trouble with the rat race is that, even if you win, you are still a rat.", which is attributed to either Lily Tomlin or some gadje at Yale university.

I am probably going to whinge on about English drivers until I get wiped out by a French granny doing 90 through Le Dorat, but the difference is startling and there is one particular English driving manoeuvre which typifies that difference and that is shoulder sitting. If you keep to the nearside lane and just pull out to overtake slower vehicles, then invariably some clown will draw up alongside you in the middle lane and sit there, despite there being loads of room for him or her to pull forward. The result is that, in defence of their average speed, lane disciplined drivers start to pull out earlier than necessary, the middle lane gets clogged and the whole thing is repeated in the fast lane.

If you are going to overtake, then overtake and get out of the way. I don't expect any signals as they are obviously not fitted to English cars, but the least you could do is to **** off and annoy someone else.

Cami took the wheel at Clacketts lane services, just after we joined the M25. She didn't actually take the wheel of course, she left it on the truck and just moved it around a bit to go round corners. Oh boy, was I glad I had become a passenger as the M25 did its usual time warp back to the Eighteenth century, with the traffic managing all of twelve miles an hour. Having got to Calais a couple of hours early, we finally got home at the time we originally expected to.

The first thing I checked was whether Dave had fitted the new window in the back bedroom. He had and made a very neat job of it. The rest of the house was in good order, but the garden looked like some primeval jungle. It is going to take a month and frequent trips to the tip to clear it back to some sort of order. A huge amount of self-seeding has taken place, Amongst the sea of weeds there are drifts of poppies and strawberry plants creeping everywhere. There are even a couple of self-seeded tomato plants in the greenhouse, so we may get a small tomato crop a little later. There were also enough blackberries, raspberries and blueberries for Cami to make a summer pudding, which was delicious.

Needless to say, we were faced with a mountain of post that had accumulated.

It didn't really take that long as most of it was junk mail, but in these recycled days, you have to separate junk paper from the junk plastic that some of it is wrapped in. There ought to be some central registry where you can sign up to never get any junk mail. The good news was that alongside twelve copies of New Scientist to catch up on, there were four new tool catalogues to pore over.

Dreaming of electric sheep

It's July in Montgomard and we are tantalisingly close to having shiny new electricity throughout the house but, in reality, our electricity supply has actually got worse. Let me explain.

The ancient old three phase system, with bare wires tacked to the walls and lights and power sockets all sharing the same circuits, was fed from a distribution board located in the bathroom. If you are going to mix water and electricity, then do it in a steamy atmosphere I always say. So part of the plan was to move the board next to our new consumer unit in the old cellar and to that end I dug a half metre deep trench from the bottom of the wall where the electricity supply cable hits the house and laid in 90mm trunking to the cellar via yet another large hole in the wall.

I am getting quite blasé about punching large holes through thick load bearing walls as I now understand how differently the loads are transmitted in these walls compared to the brick walls we have in England. The easiest way to describe it is to say that the irregular shapes of the granite boulders form hundreds of arches stretching in every direction within the walls. Well, not every direction as there are probably not any that take the loads upwards, but you know what I mean.

Our problem is that the electricity company (EDF) has not come back to us with a price for moving the supply. The sad thing is that we know roughly what the price will be (they have standard prices for this sort of thing) but cannot contact them to say yes until they contact us to formally give us the price and they cannot find the form we completed asking for a price, so we have had to ask a second time. But it gets worse. We asked for the quote to be sent to Mongomard but, of course, we are no longer there. Perhaps it will be waiting when we return in September, although I have a bad feeling that this could turn into a real saga that I will have to write up in runes. Turn in your grave Kafka.

As a result, we still only have one phase of the old three phase system connected to all the new single phase outlets, which means that we can have a maximun of only two kilwatts connected to them at any one time. Put the iron and the kettle on at the same time and the circuit breaker will trip. Why do we only have two Kw? Because of the way that electricity is sold in France. You buy a maximun wattage as part of your plan and the greater the maximum, the greater the standing charge and the higher the unit cost. The minimum concurrent loading you can buy is 6Kw and that is what many people opt for. The unusual aspect of the pig farm is that the feed is three phase, so it has three main fuses and circuits are attached to each, giving three single phase circuits of 2Kw. Got it?

We still have one remaining old outlet connected to one phase and have the fridge plugged in to this, otherwise we would have a real problem using tools. We have taken another phase for the new circuits and the third phase is currently unused.

The French supply system was set up so that the state could control demand to make things easy for bureaucrats, but it has the unintended consequence in these green economy times of fitting in nicely with the new idea of controlling demand to save the planet. In England, we are going to find it more difficult to curb demand when we pay less on average for every marginal increase in usage.

Once we get EDF sorted, we will have a single phase supply of six kilowatts and we could of course change our plan to increase the maximum wattage. Given that we are currently living on two kilowatts plus the fridge without too many problems, it seems that we won't really need more than six until either I move my woodworking machinary across, or we finally get around to buying a cooker with an electric oven.

Every trade has a specialist set of tools and the electricians trade is no different. It is particularly important to have the correct tools for installing sophisticated 21st century electrical and communication circuits and here they are.

The Kango hammer is vital for getting through the concrete floors, when routing the cables across doorways and the extra long drill bit that is fitted to my heaviest hammer drill, allows you to see when it emerges from the other side of a 500mm thick wall. However, the most useful tools are the hammers and chisels and the long crowbar on the right. When you have done all the kangoing and chiselling that you can, you still have to force out large pieces of granite and nothing works better than a long steel lever.

Behind the tools, you can just see some of the results, a double gang power socket on the right and an RJ45 socket on the left for our computer network. Why, you might ask, are we installing a wired comms network in these days of 802n wireless routers? Did I mention the 500mm thick granite walls. Even in England, with brick walls, we have wireless problems with the steel beams that have replaced some walls. In France the router is three rooms, that's one metre of solid granite, away from where the laptops will usually be used, so I am taking no chances.

This picture shows the new consumer unit on the left of the backing board and the comms unit on the right. On the floor, you can see two pieces of red 90mm trunking coming through the wall, which will be cut to length and fastened to the bottom of the board. One brings the supply in and the other will take the supply out to the workshop. The EDF meter will sit below the comms unit.

The comms unit that has been installed is a neat affair that handles all our TV, phone and computer hookups. It means, for instance, that changing from ADSL broadband to satellite broadband involves no more that moving an RJ45 plug to a different socket and, for a nineteenth century cottage in the middle of the country, that's pretty slick.

In fact the whole electrical installation is exellent. I have written before about how taken I am with French electrical regulations, but I am also impressed with the kit that has been developed to meet them. The basic design is the same as U.K. kit as it is the same 240 volt a.c. system, but the little details are well thought out and the setup has a solid, well built feel. Conversion of an on/off light switch to a rocker switch is as simple as installing a spring.

Of course, the success of the whole process depends on a good electrician and we have a great one. Charles is French, but has spent some of his life in England, Germany and various other places, The end result is a completely bi-lingual and very erudite electrician, who came to us with a good reputation locally and has only have increased that reputation with the work he has done for us.

As always, I like to think that I contributed something by having a fairly well developed plan of what we needed, complete with diagrams. But Charles took that plan and translated it into actual cables and sockets that gave us what we need now and has given us the means to expand in the future,So, hats off to Charles and, if you are thinking of moving to the Limousin, you can contact him here: charleselec@gmailcom.

A long way from Kansas

Only in France would you come across a reference to the 1968 Paris riots in a DIY magazine, Every culture embeds philosophy into its everyday language, but in France it is obviously articulated. Ordinary people have actually heard of philosophers. Only French philosophers of course but even so, imagine asking someone in in the middle of Cheshire what they thought of Bertrand Russell.

This understanding of philosophical concepts animates the French language. A whole conversation can be had with just two words "ça va", which literally translated means "this goes" or "that goes", but the literal translation will rarely get you close to what these words really mean in French. As a question their meaning ranges over such things as "How are you?", or "Are you better than you were yesterday?", or "Isn't it a great day?" As an answer they can mean, "I'm fine", or "I'm OK I guess", or "It's a bloody awful day, the taxman just called."

So answering "Ça va" to the question "Ça va?" means understanding the shades of meaning involved in articulating those two words in a particular way and shades of meaning are the essence of philosophy.

I am also just beginning to get the way that the French language lines up the words according to case and tense. In Germanic languages like English, we just keep adding words until it all makes sense, but in French, Italian and Spanish they modify words to suit the circumstances, First off, this appears infernally complicated. In English, "you are" in the singular is the same as "you are" in the plural, but in French it is "tu es" and "vous etes". In fact, it is even more complicated, because you would only use the singular form with children, animals (don't ask me), family members or people that you knew very well. Imagine: "Do I know this person well enough to say 'how are you?' or should I say 'How are you?'"

But in fact, for every part of the language where the French way appears difficult, there is another part where it is much simpler. I could bore you with a long list of where each language is easier or more logical, but remember that language evolves according to specific human communication needs, rather than by any rules of logic. Grammar is just a hotch potch that tries, not very successfully, to put some order into the way that we communicate. A hopeless task. But still, only another ten years and I shall be fluent in French; I wonder how much longer it will take to become fluent in English?

I came across an unexpected language fact the other day. Richard I, that lionhearted king of England. not only could not speak a word of English, but would have had some trouble understanding French as well, His native tongue was 'langue d'Oc', or Occitan, the language of Languedoc up until at least the fourteenth century. Languedoc is in the south of what is now France and part of it fell into the duchy of Aquataine, which became English when Richard's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine, married Henry II.

Oh, those three lions on English football shirts, symbol of Richard the lionheart, well they're not: Lions that is. They're leopards, but in haraldry, there is little difference between leopards and lions as, in the middle ages, leopards were thought to be crossbred from lions and panthers and are usually shown in heraldry with manes.

How the hell do I mode d'emploi it

An update to my life would not be complete without some reference to tools and this year I have made some major acquisitions including a Michelin VXC100 air compressor, a trolley jack, an engine hoist and a scythe.

Now most people spend their whole lives blissfully unaware of air compressors. If you are in the motor trade, or make television programmes about American custom motorcycles, then you will know and possibly love them, but why would one raise its head above my horizon. The answer is 'les poutres'(pronounced 'lay pootra').

Poutres are large wooden beams in French and our cottage depends upon them. We have a huge oak beam, some 450 by 250 mm (18 by 10 inches for you imperialists and isn't it funny that the U.S.A., a country founded on anti-imperialism should be the only major country still using imperial measures). Our beam runs North - South across the axis of the house and supports everything above the ground floor. Across this are laid the equivalent of English first floor joists, except that they are also in oak.

To be fair, it is no longer that unusual to find oak beams in English houses, but in England that means that either the house put up Shakespeare for a night or it is about to appear on an episode of 'Grand designs'. Not many council houses are built of oak and what we are living in is an early nineteenth century sort of council house. A house that a farmer provided for his workers to live in.

Anyway, at some time in the past our oak beams were painted with black paint, which has penetrated into all the grain patterns and nail and worm holes. No amount of surface sanding is ever going to get into the crevices and so the only recourse is to sand blast them.

We also have a number of iron radiators, that we want to recycle. Once they have been stripped of decades of paint and cleaned out internally, they will give us many years service. Again, only a sand blaster is going to get into all the crevices, but what I have also discovered is that only a trolley jack is ever going to lift them off the wall They are cast iron and even the smallest of them weighs at least sixty or seventy kilos.

I bought a low level trolley jack and that just slides underneath them so that they can be jacked off the huge wall hooks that they hang on and rested on wooden blocks. Once they are clear of the wall, the engine hoist can lift them onto a trolley for transport to the workshop. This does mean that I now own two engine hoists, one in each country and neither of them will ever hoist an engine, but if you work on major renovation on your own. or want to move woodworking machinary around, then you need all the help you can get.

What is fascinating about these radiators is that they are bolted together. Each of the sections of six pipes and a header and footer is held in by a threaded nipple that can be removed using a lug wrench. You remove that large nut you can see, where the radiator valve is attached, insert the lug wrench to the point you want to disassemble and turn to release the nipple at that point.

What this means is that you can make the radiator any length you want, simply by adding or subtracting sections. Once, that is, you have managed to move them somewhere suitable to unbolt them, have remembered to pack your largest wrench and have found a source of supply for radiator lug wrenches. We have been quoted €800 to buy one of these radiators new and we have five, so it is tempting to refurbish them, sell them on and replace them with steel at about €200 a pop. But, as I have already said, this renovation is not just about money and our refurbished iron will look great against the earth coloured lime wash of the walls. Anyway, back to the compressor story.

One final example of our need for air at high pressure is that the beautiful granite and touf walls of the barns have been hastily smeared with cement in some places; days of work to remove with a chisel, but a few hours with a sand blaster will clear it with no problem.

What I hope is becoming clear is that it is impossible to consider a civilised life in the Limousin without owning an air compressor powerful enough to feed a sand blaster. My purchase of one has nothing whatsoever to do with my fetishistic desire to own every single tool ever produced on the planet.

With air compressors, size does matter. Not so much the pressure that it can produce, but the volume of air that it can push through a tube at a nominal 7 bar of pressure. As with most aspects of life, size costs, so I forked out for a top of the DIY range Michelin that can put about 300 litres of air a minute through. Not industrial strength, but more than enough for what we want. Once I worked out how to get it out of the truck without a forklift (which is how it was put in), then we were off and running. Within a year we will be wondering why everyone doesn't have one. Either that or we will have stripped our fingerprints off, forgetting which way the nozzle is pointing.

What I was not looking forward to was laboriously translating the operating manual, but hey, we are all Europeans now; so the operating manual, as well as being in Estonian and Finnish, was also in English; even I could understand the mode d'emploi.

There is a sad sequel to the compressor story. It's broken. Some grit got past the air filter and jammed a valve open. I have dismantled it and cleaned it out and the cylinders do now suck instead of blow, but I had to put it back together without having any new gaskets and one of the old ones is blowing, so we only have about half pressure.

I bought a Michelin because I thought that a French marque would be easier to maintain in France but, it turns out that Michelin do not make compressors in France; they buy them in from Italy and, whilst you can get parts for them, you certainly can't get them at your local machinary store. The moral of the tale; buy local and check that local really means local. So it's a pause in radiator refurbishment until the gaskets arrive from Italy.

But what, I hear you ask, about the scythe? Well I certainly didn't expect to be buying a scythe at this time in my life, not even to try to outgun the grim reaper; but we have a 1,000 square metres of garden that we aren't going to have the time to cultivate this year and the weeds, despite this being the worst ground we have ever tried to garden on, are growing like crazy.

Why don't I use a petrol driven brush cutter, as, of course, I have one of those? Two reasons: Firstly, if you hit a hidden rock with a brush cutter, the rebound makes your arms ache and it takes twenty minutes to get the ding out of the blade. Secondly, I am only allowed to make noise between 09:00 and 12:00 and again between 14:00 and 17:00. Don't ask me why; something to do with fitting into the community, so I have to devise ways of working relatively quietly and nothing can be quieter than the swish of a scythe.

Here I am taking first tentative swipes at the wilderness. I first used a scythe some forty years ago when I spent a summer working on the railway. One of our jobs was to mow the embankments and a scythe was what we were issued with to do the job. Efficient scything depends upon three things: Angle of attack, rhythm and sharpness.

The angle of attack between the blade and the stalk of a weed should be no more than 45%, ideally, somewhat less as you are not trying to chop, but to slice. There should be little effort involved; the weight of the blade will be enough to do all the cutting, but you do need to swing it in a wide arc to get the blade moving at speed and, every thirty minutes or so, you need to stop, lean on the scythe and wipe a sharpening stone along the length of the blade. It also helps if about every hour, you stop and take a swig from the apple brandy jar you have stored in the shade of the poplar tree you can see behind me.

There are no correct bevel angles for scythes, you can just hear when it is sharp. Those of you who know about scythes will have seen from the picture that the blade looks rather short. In France, they sell a half blade, which for the stony, uneven ground that we have, results in a lot less dings in the blade, although it takes longer to mow a meadow.

Where did I get such an esoteric implement? Did I have to go to a specialist 'ancient farming tools' shop? No, I just walked into the local France Rurale store and there. along with the shovels, forks and rakes, were the scythes. Not complete scythes, you understand, but the unmistakably shaped handles and a selection of blades to fit into them.

And some gardened on stony ground

Walking across the garden in Mongomard on a sunny day is like walking across a field of tiny diamonds as the grains worn from granite bedrock sparkle in the sun. Unfortunately, the grains come in all sizes, some up to half a metre across. Every cubic metre of what may loosely be described as soil is made up of the following by volume: 50% lumps of rock, 24% sand, which is just very small lumps of rock, 22% clay (even tinier lumps of rock) and 4% organic matter.

If you dig down a spade depth and remove the larger rocks, the ground level drops by half a spade depth; except of course that there is no way that you can dig with a spade. To clear the ground, there are two options; a plough or a pickaxe and we don't own a plough, yet.

In fact, Cami made heroic efforts with a small border fork and managed to clear enough for a row of garlic, some lettuces. a few herbs and a couple of tomato plants. We can't try anything else this year as we won't be here for the main watering season.

The stakes they use for tomato are a lot stronger here than I would usually use in England, in fact Gerard uses fence posts. but then I guess he has a lot of those to spare. I think the tomato post size is because they go in for big, heavy cropping tomatoes rather than the cherry sort that I usually attempt.

Vegetable patches are a way of life in this part of the country and it is amazing how well cared for they are. Everything is in neat rows and there is not a weed to be seen. Unlike our efforts, where you can see the weeds climbing over the stone ramparts that Cami erected. Its like being in a vegetable wagon circle with thousands of ramaging indian weeds creeping ever closer to our helpless tomato plants. We don't intend to resort to any chemical cavalry, so its back to the pickaxe.

Just before we left Montgomard to return to England Cami lifted her garlic and strung it into a nice plait that should keep us in garlic over the winter.

More renovation

I have been hacking away at a pigpen door to make it tall and wide enough to get the oil tank for the central heating system into it. There are three pigpens at the side of the house that we are going to keep and this one, which is the biggest, will be used for storing garden equipment as well as the central heating tank.

The original height of the door was level with the window on the right, as the large graze on the top of my head can testify. The final door size will be two metres high and about a metre and a half wide. Big enough to drive my garden tractor in. I don't yet have a garden tractor and there is no money in the budget for one, but you have to plan ahead.

Inside, the pigpen is fairly large, about the size of sixteen garden tractors. OK! I know that garden tractor is not an SI unit of measurement, but I have to make sure that the words are heard by Cami as often as possible, so that when I finally broach the subject, she will already be comfortable with the concept.

The height at the back wall is some four metres (eh, that's about three garden tractors, one on top of the other), so a very useful storage area, particularly if you have a garden tractor to store.

By now you are probably asking what the difference is between a garden tractor and a ride-on lawn mower. Clever you; not too many people bother to ask and I can't think why. To be a tractor, the vehicle must at least have a power take-off (PTO). This is a shaft, driven from the engine, to which towed tools can be connected. Things like seed drills, muck spreaders, etc.; anything which needs to be mechanically turned or moved. Tractors can also have hydraulic connections for back hoes and dozer blades, etc.

There are some high end ride-on mowers that can be considered tractors and some of the expensive ATVs and quad bikes have a form of power take-off, but it is much cheaper to buy a compact tractor and tow a mower behind as needed. So now you know.

Before the compressor broke, we started renovating the radiators. Here is the first one on its long journey from the house to the sand blasting station in the barn. It's a bit like a space shuttle moving at cape Canaveral in that, because of the uneven ground, we have to move very slowly and carefully to avoid it tipping over.

An interesting obsrvation about gardening in this part of France is that all tools and equipment are much stronger and heavier than those you buy in the garden centre in Reading. The little garden cart that the radiator is sitting on is designed to carry 400 kilos, thats like four heavy people, much more than you would expect for such a small garden cart and, of course, it has a fitting such that it can be towed by a garden tractor. The garden fork I bought has tines close to half an inch in square section and, once you start digging, you can see why.

Since the first radiator photo was taken, I have modified the cart, replacing the plastic tipping bucket with a plywood flat bed, so that we can carry some of the longer radiators. But I don't yet have a garden tractor to tow it.

The story so far

We are now in August and we have about another month of renovation ahead of us this year. We will go out to France in mid-September and come back before the real cold weather sets in in Novermber, as the central heating is not due to be completed until next April. So now is a good time to step back a bit, crush the rose tinted specs underfoot and check whether the project really looks as though it can be successfully completed within the specifications set out for it. Which were:

- A safe haven for our savings.

- A potential retirement home.

- A giant exercise machine.

- Time in the country.

- A chance to experience a different way of life.

Financially, everyhing is on course. We have changed the order of things and have had to accomodate a new central heating boiler into phase one but, where we can compare like for like with our original estimates, we are about 3% under budget, with about half of our total renovation money spent or committed. The many hours of researching French prices has clearly paid off and, as all but one of the big ticket items are now behind us, we should be able to easily control spending in phases two and three.

I haven't got quite as far forward as I wanted this year, but we don't face any time bottelnecks as long as I finish channelling for the central heating this September. There is no reason to suppose that we won't complete the project within the three years we set ourselves.

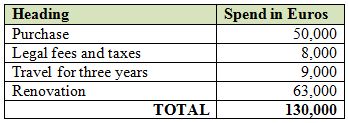

So, we will end up with a large three bedroom, two bathroom cottege of about 170 square metres, fully insulated and with new drainage, plumbing, heating and electrics, for about €130,000, not counting the cost of furniture. That breaks down as follows:

Looking at other restored properties in the area, gives us a sale price of between €150,000 and €170,000 so, at the low end, I will have earned €20,000 for three years hard work. Not a huge return for all that effort, but that was never the point of the project. At least we know that, if we do have to sell, we won't lose out financially and our money is safely encased in granite rather than leaking slowly out of a bank account.

One of the important reasons for starting this project was to give me a more interesting way to keep fit and that it has done. I have put on a bit of weight this year, but that is largely through replacing fat with muscle and I am still some thirty kilos under my maximum fat boy weight. My heart is going fine - the doc says that it has decades of life left - and blood pressure, whilst still a bit high, is much better than it was. No sign of any diabetic or chlorestorel problems for two years now and that is a sure sign of enough exercise.

We have certainly experienced a different way of life. It's slower, friendlier and puts more emphasis on family. It is very easy to live on fresh food, locally sourced and there isn't a Starbucks or McDonalds within 30 kilometres. Although I admit that I do miss not being able to get a take away curry.

We can therefore tick all the boxes, but it is not idyllic. Dog shit and flies are the biggest problems and it will not be possible to solve either of these problems completely. The other major drawback is that we cannot live in Mongomard without a car. Whilst, we can walk or cycle to the nearest small town, which is only some three kilometres away, it is only really possible to do food shopping there. For anything else, it is at least a fifteen kilometre drive.

Will we move to Montgomard permanently? I have no idea. I would move like a shot and hang the consequences, but Cami is a little more prudent, so we will wait till next year, before we attempt to make that decision. In the meantime, I can't wait to get back to banging big holes in things. Roll on September.

Last updated 23 August 2011